|

| Richard Feynman |

I wish to explain my position here in brief. It is not quite a full picture, and like most things outside of logic and mathematics, it is difficult to see how it can be made objectively normative. Furthermore, it completely omits the sorts of arguments and pathways that led me to some of the premises in this framework originally - a path that involved the methodological scepticism of Descartes, some study of philosophy, history and science. That story would be my best attempt at a foundationalist approach to Christianity - and I think it gets one relatively far, certainly to the point of being some sort of Christian. But it does not truly ever arrive at Christianity. I have instead found the position I hold now to be far more compelling and satisfying, even if it will alienate certain conversation partners.

To begin, I must quickly introduce what epistemologists mean by knowledge. Precise definitions vary because of some rough edges, but the classical definition still holds relatively firmly: knowledge is true and justified belief. That is to say, that some proposition constitutes knowledge in the case that the knower believes the proposition (one cannot know what one does not even believe), the proposition is in fact true (one cannot know a falsehood) and finally, one is justified in believing the proposition. What separates knowledge from belief is that the belief is true, but perhaps more importantly, that the knower actually has sufficient reason, or justification, to believe the proposition. Not surprisingly, some of the fiercest debates in epistemology seem to be around theories of what constitutes justification.

Very simply, I will term my position Christian reliabilism. Reliabilism, in the sense in which I will use it, refers to an epistemological theory of justification which says, in a somewhat crude form, that a belief is justified if it arises from generally truth-giving (or "reliable") faculties or sources, in the absence of evidence to the contrary. For example, I am justified in believing that I am sitting on a chair because I sense that this is the case with my sense of touch and sight. If there were evidence that I was dreaming, then I would no longer be justified in believing I am sitting on a chair.

Reliabilism is a broad family of theories of justification, and can actually be used in a broader sense than just justification. One reason it is powerful is that it is probably the only practical theory: the two other major families of competing theories are foundationalism and coherentism, both of which are excellent, but neither of them can really be thought of as "day-to-day" theories of justification. Foundationalism is very intuitive for people like myself who study mathematics, since it consists of the view that knowledge is built out of self-justified, basic beliefs. These could be said to correspond to what mathematicians call axioms. Descartes is surely the most famous and clearest foundationalist. Coherentism is a less ancient theory, but it is one which tends to appeal to scientists (as well as others) because it holds to a view that is somewhat similar to the approach taken in the natural sciences: coherentism is about finding justification in a coherent set of beliefs. A belief is justified if and only if it forms part of a coherent set of beliefs. Although the natural sciences involve other principles, such as Occam's razor, that a theory be coherent with all the data (both the data that has already been obtained, and the results that the theory predicts) is what defines a good scientific theory.

I struggle to see how truly self-justifying propositions can form a proper basis for knowledge without an impractical degree of scepticism. I doubt that even such basic things as the existence of the external worlds, or other minds, or perhaps even of the self, could be proven from self-justified propositions. So whilst I am drawn to foundationalism by my mathematical training, I cannot support it as a practical theory of justification. Coherentism is a theory I would be biased towards accepting, since its internalist structure makes it fairly straightforward to be a Catholic. But alas, I cannot see how it can be ultimately defended; it has elegance, but I see no way of bridging the gap between what reality seems to be in itself, and a coherent set of propositions. Elements of coherentism feature to some extent in many forms of reliabilism, however, and so coherentist theory may appear implicitly in what follows (in particular, note that the clause "without evidence to the contrary" given above in regards to reliabilism is essentially a statement about coherence).

Now, what constitutes a reliable faculty or source of truth is the area where Christian reliabilism is set apart from non-Christian reliabilists. It considers there to be three broad sources of truth: reason, experience, and Christianity. Reason is reliable as a source of truths, for instance, in mathematics or logic. Experience, by which I mean sensorial experience or experience of the empirical, is a reliable source of truths, for instance, in the natural sciences. God is a reliable source of truths in all areas, though I do not know of anyone who argues that God is a source of truths in actuality, since God is generally said to have revealed things of a particular kind, if any.

Probably the first objection one might have to adding divine revelation to the old empirical-rational duo of reliable sources is that divine revelation (sometimes called special revelation, or hereafter, just revelation) does not build off the others. However, whilst that line of critique would be fruitful if I were advocating foundationalism, it is somewhat irrelevant to a reliabilist. This can be seen from mere consideration of the other two: someone who denies the existence of the external world could just as well argue that experience is not a reliable source of truth, because it is not giving truths about anything that actually exists. Arguing that reason is a reliable source of truth is more difficult, because all arguments make inferences that are deemed valid by reason, but somebody stuck with a Cartesian demon would, nonetheless, doubt their own capacity for rationality. At bottom, both reason and experience must be deemed to be properly basic by the reliabilist - the foundationalist may mutter in despair, but they can do no better.

The Christian reliabilist, then, adds God to the list of properly basic reliable sources, and specifically, God as revealed in Christianity. Supposing God to exist, it seems obvious that God is a reliable source of information. Furthermore, there exists an parallel between the existence of the external world and the existence of God: whilst I think the existence of God can be proven, many dispute that arguments I find sound truly are sound, just like how philosophers such as G.E. Moore believed they could prove the existence of the external world, and yet, many dispute the arguments he offered (including myself). It could be said that, like the existence of the external world, the existence of God must be assumed. Whilst I have some discomfort at holding that position, particularly since I think the existence of God can be proven,* it can nonetheless be held with intellectual rigour, so long as it is granted that one is justified in believing in the existence of the external world without a priori proof.

The second objection is far more substantial, in my estimation: I have used God-as-reliable-source and Christianity-as-reliable-source somewhat interchangeably. But they are not the same, as a Muslim or Jew (et cetera) would inform. The same point made above could be a fruitful venture, that is to say, that one must assume Christianity to be properly basic, and yet, that route is supremely unsatisfying. The most obvious reason why that is the case is that the truth of Christianity is not like the truth of the existence of the external world, or God, but of a choice between multiple different competing sources for the title of divine revelation.

The difficulty could be resolved by trying to dip into the other theories of justification: I could attempt the foundationalist route, as I did when I became Christian, and argue from historical Jesus studies, in particular, any evidence for the resurrection. A similar approach could be taken for some other path from reason and experience to Christianity in terms of foundationalism, although I cannot think of any that are uniquely Christian and sufficiently powerful.

Or via the coherentist one, I could assume that God has "spoken" through some religion, and test them all to see which presents itself as most coherent. That the union of secular fields of knowledge and Christianity yields a powerfully coherent set of propositions, including with historical Jesus studies, keeps my mind at rest whenever I have major doubts about things, and yet, as I said, coherentism leaves me unsatisfied in general as an epistemic justification theory.

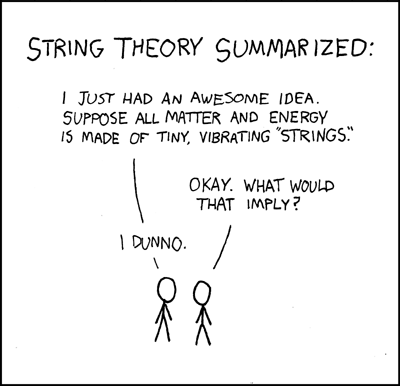

This second objection is not, in any case, unsurpassable since one could in principle assume Christianity is properly basic. Objections such as "given Christianity is true, what follows?" - in the same vein as the satirical xkcd comic strip on string theory below - are also important.

As one person noted to me, there is an important problem of interpretation: creedal statements like "Jesus is the Son of God" can be variously understood. What does it mean to be the Son of God? (One would naturally jump to some sort of sexual reproduction, which at least to some extent, would be completely mistaken) What does that imply about Jesus, other than origin? (The Arians, for instance, generally did not deny Jesus' sonship, but they did deny his divinity). If there is a difficulty in interpretation, there is a difficulty in understanding what is said to actually follow from the view that Christianity is a reliable source of truth. To a large extent, but not fully, this objection is met by Catholics in reminding the protester that the Church is herself a "living voice" - Christianity, in the view of Catholics, is not a religion of the book. As the Catechism quotes St Bernard saying: Christianity is the religion of the "Word" of God, "not a written and mute word, but incarnate and living". (CCC 108) And yet, that does not always yield perfect interpretation.

So Christian reliabilism has some issues that remain outstanding. Still, I contend that they are largely rough edges which can be fixed. One issue, however, remains crucially outstanding: Christian reliabilism is not objectively normative. By that I mean, whilst I can hold to it with intellectual rigour, I see no reasons within the system that would convince someone who did not hold to it. Whilst the same could be said, once again, about those who deny the existence of the external world, and to a large extent, absolute objective normativity is generally not thought to be possible, this is a theory which involves a much more ambiguous series of entry points. To this issue, I will return at a later date.

* It is actually a de fide teaching, I am told, of the First Vatican Council. Strictly speaking, though, since God is beyond what the usual arguments show (except, were it sound, the ontological argument), I do not believe the existence of God can be proven, only the existence of a being which is remarkably like God.