Search This Blog

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Christianity. Show all posts

Friday 2 May 2014

Uniqueness and Sanctity

It is among the most popular messages of films, television, songs and culture at large: be yourself! Love the person you are. Being true to oneself is among the highest virtues, it would seem. Exactly what one hopes to achieve with doing so is not always so clear: Psychology Today had an article on that challenged "Dare to be Yourself.," there is a WikiHow article on how to do it, and whether it is actually a Buddhist principle or not, LittleBuddha.com has an article on what it means and how to do it. Everyone seems to think "being yourself" is a great idea.

Lao Tse, the legendary founder of Taoism writes “When you are content to be simply yourself and don't compare or compete, everyone will respect you.”, whilst on the other hand, others (such as Frederick Douglas) suggest that not caring about winning other people's respect is the key to being oneself, and so Lao Tse's "incentive" would cease to be an incentive if we reached that point of being ourselves. For people like Douglas, it would be like advertising chocolate by telling people that it will seem great whilst they are buying it, but they will not want it when it comes to chomp time. Meanwhile, philosophers usually worry more about problems of personal identity, not in the sense of realisation of some hidden "you", but figuring out who "you" is right now, and who "you" will be tomorrow (if it is the case that "you" actually even exist tomorrow - some, like David Hume, would say "you" would not).

The Christian has a very unique spin on whether or not it is important to be oneself and what that means. For Christians, being yourself is crucial, but you are not who you think you are. For instance, you might think that you are a skilled baker, and so being yourself is making excellent bread. Or you might think you are a quirky student, so being yourself is being quirky as a student. Christianity says these matters are peripheral to who you are, they are you accidents, not your substance. We see who we are not by looking inward at what we are like, but by looking outward at Christ. In Jesus we see the image of real humanity, and it is in him that we find who we are, as well as who we are meant to be. This is why we say in the Nicene creed "true God and true man" - Jesus is the truly human one, he as sinless, as perfect, is the real human. We, through our selfishness, our pride, our greed, have broken our humanity.

So we must reclaim that humanity in light of Christ. This is what it means to be a saint: not being really really nice, but being transformed into what we were meant to be, ridding ourselves of our human brokenness and instead taking on our new humanity from the only one who has real humanity. Uh oh. That sounds a bit stifling, right? I mean, it is back to the whole "being someone else" thing, and surely that is not "being yourself", right? Not so, not so. Chesterton was right when he said: "It is a real case against conventional hagiography that it sometimes tends to make all saints seem to be the same. Whereas in fact no men are more different than saints; not even murderers."

If you read the lives of the saints - which can be a hard thing for some of the older ones, because of the pious legends and the homogeneity that comes from the stylists who wrote the lives up for us to read - you will find that over and over again, they are incomparably unique and wholly alive. Which can be a bit of a shock if you have been brought up thinking of saints as this:

Let me take just one example, a person close to my heart, who is well on his way to canonisation but who also made the mistake of thinking of the saints as this fairly homogeneous group of men and women. He thought he was not a saint because he was not like that group. He was wrong, because that group evades stereotyping. I speak of John Henry Newman, who wrote this when told that others thought him a saint:

"I have nothing of a Saint about me as every one knows, and it is a severe (and salutary) mortification to be thought next door to one. I may have a high view of many things, but it is the consequence of education and of a peculiar cast of intellect—but this is very different from being what I admire. I have no tendency to be a saint—it is a sad thing to say. Saints are not literary men, they do not love the classics, they do not write Tales. I may be well enough in my way, but it is not the ‘high line.’ People ought to feel this, most people do. But those who are at a distance have fee-fa-fum notions about one."

He was so different to the saints he knew that he thought he could not have been a saint himself. And behold! It was only a few years ago that the Pope made insinuations about him being declared a Doctor of the Church, a title given to those whose theological writings and teachings have enriched the Church - but he is not just a great theologian, for all Doctors of the Church are themselves canonised saints - and sanctity is not merely a matter of intellectual acuity.

The saints are completely themselves because they have heeded to that perfect image they were made in. St Paul writes to the Colossians that Christ is the "image of God", and the author of Genesis said humans were made "in the image of God." It is in recovering that archetype of their humanity, that they found themselves, human as they were, being even more fully themselves. And far from stifling them, they flourished! This new humanity that we see in Jesus is a glorious one. It was not in vain that Pope Benedict XVI said:

"The world promises you comfort, but you were not made for comfort. You were made for greatness."

In short, the saints are those who are fully themselves. They found themselves by denying what they might have thought to be themselves, the sum of their interests and desires, and in that self-denial, found themselves in Christ. They found themselves in the wholeness of their humanity, and so they had to find themselves outside themselves. We, also, must be ourselves, and like the saints, find our humanity in Jesus Christ, who has it perfectly.

Loving the Lovely and Unlovely

It has become commonplace, at least among young idealists, to talk about "always finding the good in someone." No matter what the person is like, they always have something good in them, they say, and we should love them because of it. Whether it is true that all people have something good in them, I do not know - probably, but perhaps not. In either case, this is not a Christian approach to loving people. Christians love as required by Jesus, who says to us:

"You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward have you? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you salute only your brethren, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect." (Mt. 5:43-48)

I have written on that before, now I want to bring out a crucial point here: nowhere does it talk about finding something good in the person to love. It just asks you to love them regardless. In fact, loving the good in others, like loving those who love you back, is easy and it comes naturally. Christian love is special love because it is predicated on the assumption that we should not love people because they are good, but simply because they are people, and it is hence supernatural rather than natural, because it is modelled on the love of God.

I have written on that before, now I want to bring out a crucial point here: nowhere does it talk about finding something good in the person to love. It just asks you to love them regardless. In fact, loving the good in others, like loving those who love you back, is easy and it comes naturally. Christian love is special love because it is predicated on the assumption that we should not love people because they are good, but simply because they are people, and it is hence supernatural rather than natural, because it is modelled on the love of God.

I have found over the months a quote from Martin Luther to be insightful into this point, from the Heidelberg disputation, thesis 28:

"The love of God does not find, but creates, that which is pleasing to it. The love of man comes into being through that which is pleasing to it."

It is all very well and good to love the good in people, and the good in people certainly makes it easier to do. Nonetheless, that is no sufficient. We must love the most horrible of people, not because they are horrible, in fact, quite independently of this. For whether a person is good or bad is not a direct matter of concern when the Christian asks whether or not to love them - the Christian does so, without asking that question.

So the Christian is called to love the person. Very well. This does not at all render whether someone is good or bad irrelevant in general. In fact, as Luther pointed out, the love of God does not come into being because it finds something pleasing to it, it comes into being because God is love, and yet it creates the good in the other person. This is important, it means that Christian love does not seek that the person remain as they are, it requires change.

It can be hard to make this point clear because we are so used to the "love of man" which Luther refers to, and that adores that which is pleasing to it already. If some attribute is already pleasing, and our love comes into being because of it, then it stands to reason that this should not change, that changing it might well make it less loveable, or that changing it implies that we did not really love to begin with. However, if our love comes into being simply because the object of that love is a person, as is the case with divine love, then love might well entail the transformation of that person into that which is good.

I think this is, at least to some extent, intuitive - it is just really hard, by the same token. For instance, we might love the alcoholic, despite them being a rotten drunkard and not so nice a person when sober, and yet we try to transform them, not despite our love but because of it. Or take the greedy person who is thrifty with giving but generous when it comes to gifting themselves - we can love the person, but not because they are greedy, quite in spite of this fact. We can love them, and so desire to transform them. In short, when we love people, we want their transformation, because people are imperfect, and love seeks the perfection of the other.

We cannot love some people for what they are (personality wise), because what some people are is often not very lovable naturally. But we can love them simply because they are, simply because they exist. They have human dignity, whether or not they have human goodness. For us who take the divine example to love all, this is what we must do. We must dissuade ourselves from "love" being "liking a lot" - we may not like whatever it is we love, because, once again, we must not simply love what who we like, but also who we do not like. I hardly imagine Jesus expected us to find something very likeable in our enemies, and then love them.

So next time someone says to me "everyone has something good in them", I might say "sure, but who cares?" Or perhaps "excellent, that will make it easier to love them." What I should not say, or think, or assimilate unconsciously is "Oh, that means I should (or could) love them." I admit, I mostly fall in to ruts of loving only those that are easy to love, and for that matter, when they are easy to love. This is just not good enough.

"You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbour and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust. For if you love those who love you, what reward have you? Do not even the tax collectors do the same? And if you salute only your brethren, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? You, therefore, must be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect." (Mt. 5:43-48)

I have written on that before, now I want to bring out a crucial point here: nowhere does it talk about finding something good in the person to love. It just asks you to love them regardless. In fact, loving the good in others, like loving those who love you back, is easy and it comes naturally. Christian love is special love because it is predicated on the assumption that we should not love people because they are good, but simply because they are people, and it is hence supernatural rather than natural, because it is modelled on the love of God.

I have written on that before, now I want to bring out a crucial point here: nowhere does it talk about finding something good in the person to love. It just asks you to love them regardless. In fact, loving the good in others, like loving those who love you back, is easy and it comes naturally. Christian love is special love because it is predicated on the assumption that we should not love people because they are good, but simply because they are people, and it is hence supernatural rather than natural, because it is modelled on the love of God.I have found over the months a quote from Martin Luther to be insightful into this point, from the Heidelberg disputation, thesis 28:

"The love of God does not find, but creates, that which is pleasing to it. The love of man comes into being through that which is pleasing to it."

It is all very well and good to love the good in people, and the good in people certainly makes it easier to do. Nonetheless, that is no sufficient. We must love the most horrible of people, not because they are horrible, in fact, quite independently of this. For whether a person is good or bad is not a direct matter of concern when the Christian asks whether or not to love them - the Christian does so, without asking that question.

So the Christian is called to love the person. Very well. This does not at all render whether someone is good or bad irrelevant in general. In fact, as Luther pointed out, the love of God does not come into being because it finds something pleasing to it, it comes into being because God is love, and yet it creates the good in the other person. This is important, it means that Christian love does not seek that the person remain as they are, it requires change.

It can be hard to make this point clear because we are so used to the "love of man" which Luther refers to, and that adores that which is pleasing to it already. If some attribute is already pleasing, and our love comes into being because of it, then it stands to reason that this should not change, that changing it might well make it less loveable, or that changing it implies that we did not really love to begin with. However, if our love comes into being simply because the object of that love is a person, as is the case with divine love, then love might well entail the transformation of that person into that which is good.

I think this is, at least to some extent, intuitive - it is just really hard, by the same token. For instance, we might love the alcoholic, despite them being a rotten drunkard and not so nice a person when sober, and yet we try to transform them, not despite our love but because of it. Or take the greedy person who is thrifty with giving but generous when it comes to gifting themselves - we can love the person, but not because they are greedy, quite in spite of this fact. We can love them, and so desire to transform them. In short, when we love people, we want their transformation, because people are imperfect, and love seeks the perfection of the other.

We cannot love some people for what they are (personality wise), because what some people are is often not very lovable naturally. But we can love them simply because they are, simply because they exist. They have human dignity, whether or not they have human goodness. For us who take the divine example to love all, this is what we must do. We must dissuade ourselves from "love" being "liking a lot" - we may not like whatever it is we love, because, once again, we must not simply love what who we like, but also who we do not like. I hardly imagine Jesus expected us to find something very likeable in our enemies, and then love them.

So next time someone says to me "everyone has something good in them", I might say "sure, but who cares?" Or perhaps "excellent, that will make it easier to love them." What I should not say, or think, or assimilate unconsciously is "Oh, that means I should (or could) love them." I admit, I mostly fall in to ruts of loving only those that are easy to love, and for that matter, when they are easy to love. This is just not good enough.

Tuesday 22 April 2014

In Defence of Christian Vegetarianism? Introduction

For a very long time in human history, there have been people who did not eat animal flesh. The ancient Greeks referred to vegetarianism as "ἀποχὴ ἐμψύχων", or "abstinence from beings with a soul", and one of the more famous Greeks, Pythagoras, was a vegetarian. In the East, both the Hindu and Buddhist traditions have strong vegetarian tendencies. Among the Christian saints, St John Chrysostom and St Basil the Great seem to have been vegetarians. More generally among Christians, St Augustine of Hippo (certainly not a vegetarian himself) notes that Christians who abstain from meat are "without number" (cf. On the Morals of the Catholic Church).

Still, neither humanity nor Christianity have by any means been traditionally vegetarian. Even the many other Christians who abstained from meat have typically not done so for ethical reasons, but as part of some form of asceticism. Nonetheless, it is necessary to examine our practices, even those which have been practised for thousands of years, and ask: is this ethical?

Having thought about this issue on occasion for about a month now, I think there are about twelve arguments of varying strength for being a vegetarian, and about a dozen objections to Christians being vegetarians, each of which is worthy of note, but none of which are, in the end, successful. Not all the arguments for Christian vegetarianism are explicitly Christian, and I would not consider them all to be entirely convincing - for instance, I do not believe in human rights, so I am far from accepting the "extension" of these to animals. However, since talk of human rights is frequently found in Christian parlance, I have included it in the list. On the other side, I doubt most Christians will readily accept explicitly utilitarian arguments, even though I tend to find these more convincing than the rights-based ones.

Allow me to briefly summarize my position: the ideal for human life is to live in a world without death, both of animals and humans, where we live at peace with each other, creation, and God. However, whilst the coming kingdom of Heaven is like that, this is not the world we live in yet. Right now, there is death, pain and suffering, and the way we live our lives must recognize this fact. However, where possible, we should try and minimize unnecessary death and pain. Hence, we should avoid eating meat. More generally, however, our food (and other) choices should take into consideration the amount of suffering that is required to produce that food, and the meat industry, in general, produces more suffering than can be justified. It is therefore not right to eat meat, since this constitutes formal cooperation with the evil of that suffering. This is a position taken in light of current meat-rearing practices, and cannot necessarily be projected onto the past.

Friday 4 April 2014

They are not the Fundamentalists - I am

When you listen in on a lot of conversations on religion, or heck, even politics, you hear it often: "s/he is just a fundamentalist!" You hear it about the young earth creationists being fundamentalists. You hear about the people who want to obey this or that old law as being fundamentalists. Outside Christianity, you might hear about suicide bombers being fundamentalists. But that is wrong. Those groups of people are not fundamentalists; I am.

Fundamentalism is about staying grounded in, or returning to, the fundamentals of an area. When I watched Shankar's video taped course "Fundamentals of Physics II" offered at Yale University originally, the title was fairly self-explanatory: here are the fundamental principles underlying physics as it exists today. Here's your classical mechanics, your thermal physics, your waves, your optics, your relativity, your quantum mechanics. These areas form the fundamentals of physics as it exists today. Amusingly, it does not cover my own area of condensed matter physics, which is no small area, but that's irrelevant to the point: these areas are at the core of physics, so the course was titled "fundamentals."

However, young earth creationism is not a fundamental component of Christianity. It is not fundamental to the Bible. Reviving some old law is not keeping the fundamentals, because that law is almost certainly not a fundamentl part of Christianity. No, no, those sometimes labelled fundamentalists should be re-thought of as peripheralists: they set aside the fundamentals to concentrate on things that are actually peripheral (if at all existant in) Christianity. You think the Scriptures dictate young earth creationism? I think you are mistaken. But if we concentrate only on that issue, we are being peripheralists, because of the seventy seven books which make up the Sacred Scriptures, such a position is insinuated in at most a handful, if at all. It is a sideline issue.

When Jesus confronted the Pharisees for emphasising the Torah's minor laws, or for invalidating the law for the sake of human traditions, Jesus was being a fundamentalist. The Pharisees were being peripheralists. This is something which Israel rich prophetic tradition had tried to tell the Israelites again and again: sure, there's a sacrificial system in place, but God desires mercy, not sacrifice, as the prophet Hosea said. Sure, there are important civic duties, but what does God demand of us? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God, says the prophet Micah. The problem with the Pharisees, at least in part, was that they could not discern the fundamental from the peripheral. They were peripheralists, not fundamentalists.

I try my best to be a fundamentalist. The fundamentals of Christianity from an ethical perspetive are the three theological virtues (faith, hope and charity, or love), of which the greatest of these is love. (cf. 1 Cor. 13) There is core principles of Catholic Social Teaching: the promotion of the dignity of the human person, the common good, subsidiarity and participation, solidarity, the preferential option for the poor, social and economic justice, the stwardship of the environment and the promotion of peace.

Of course, being a Catholic fundamentalist is not just about the radical call to love others. There are doctrines involved. Much of the fundamental doctrine of the Church is in the ancient creeds: the Nicene-Constantinople creed, for instance, which is said each Sunday at Mass. There is the Eucharist, and other sacraments.

There is Jesus. Jesus who is human and divine, "true God and true man," who was incarnate in the womb of his mother Mary. There is his teachings and preachings, his ministry, his good news. That Gospel, for which St Paul gave the first anathema if anyone dared change it, is revealed only in Jesus, the Word incarante, the Lord and Redeemer. This Gospel is that of which Pope Francis wrote:

"The Joy of the Gospel fills the hearts and lives of all who encounter Jesus. Those who accept his offer of salvation are set free from sin, sorrow, inner emptiness and loneliness." (EG 1)

These are some of the core things, these are the fundamentals of Christianity, they are core to the Church. Complaining about this word usage may sound like just a simple whine, but it has important consequences about how we think about the issue. We are lulled into the thought that, when Christians concentrte on peripheral things, but are called fundamentalists, that they are the ones taking Christianity seriously. If that is true, and what is now thought of as Christian fundamentalism really is just taking the same line as the Pharisees, then one can only be a "good Christian" by deviating from Christianity. One is only good insofar as one is not actually Christian. This is a dangerous state of affairs when the matter should be exactly the other way around: the fundamentals of Christianity are not young earth creationism or following some arcane old covenant law, so following them or not has nothing to do with fundamentalism.

All this goes to say something very simple: that Christian fundamentalism is, I think, good. It is a problem, however, when one confuses the fundamental for the peripheral. That which was meant to be at best a tiny corner, became the centerpiece. No wonder the whole lot was ruined.

|

| Prof. Shankar - what a legend! |

However, young earth creationism is not a fundamental component of Christianity. It is not fundamental to the Bible. Reviving some old law is not keeping the fundamentals, because that law is almost certainly not a fundamentl part of Christianity. No, no, those sometimes labelled fundamentalists should be re-thought of as peripheralists: they set aside the fundamentals to concentrate on things that are actually peripheral (if at all existant in) Christianity. You think the Scriptures dictate young earth creationism? I think you are mistaken. But if we concentrate only on that issue, we are being peripheralists, because of the seventy seven books which make up the Sacred Scriptures, such a position is insinuated in at most a handful, if at all. It is a sideline issue.

When Jesus confronted the Pharisees for emphasising the Torah's minor laws, or for invalidating the law for the sake of human traditions, Jesus was being a fundamentalist. The Pharisees were being peripheralists. This is something which Israel rich prophetic tradition had tried to tell the Israelites again and again: sure, there's a sacrificial system in place, but God desires mercy, not sacrifice, as the prophet Hosea said. Sure, there are important civic duties, but what does God demand of us? To act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with your God, says the prophet Micah. The problem with the Pharisees, at least in part, was that they could not discern the fundamental from the peripheral. They were peripheralists, not fundamentalists.

I try my best to be a fundamentalist. The fundamentals of Christianity from an ethical perspetive are the three theological virtues (faith, hope and charity, or love), of which the greatest of these is love. (cf. 1 Cor. 13) There is core principles of Catholic Social Teaching: the promotion of the dignity of the human person, the common good, subsidiarity and participation, solidarity, the preferential option for the poor, social and economic justice, the stwardship of the environment and the promotion of peace.

Of course, being a Catholic fundamentalist is not just about the radical call to love others. There are doctrines involved. Much of the fundamental doctrine of the Church is in the ancient creeds: the Nicene-Constantinople creed, for instance, which is said each Sunday at Mass. There is the Eucharist, and other sacraments.

There is Jesus. Jesus who is human and divine, "true God and true man," who was incarnate in the womb of his mother Mary. There is his teachings and preachings, his ministry, his good news. That Gospel, for which St Paul gave the first anathema if anyone dared change it, is revealed only in Jesus, the Word incarante, the Lord and Redeemer. This Gospel is that of which Pope Francis wrote:

"The Joy of the Gospel fills the hearts and lives of all who encounter Jesus. Those who accept his offer of salvation are set free from sin, sorrow, inner emptiness and loneliness." (EG 1)

These are some of the core things, these are the fundamentals of Christianity, they are core to the Church. Complaining about this word usage may sound like just a simple whine, but it has important consequences about how we think about the issue. We are lulled into the thought that, when Christians concentrte on peripheral things, but are called fundamentalists, that they are the ones taking Christianity seriously. If that is true, and what is now thought of as Christian fundamentalism really is just taking the same line as the Pharisees, then one can only be a "good Christian" by deviating from Christianity. One is only good insofar as one is not actually Christian. This is a dangerous state of affairs when the matter should be exactly the other way around: the fundamentals of Christianity are not young earth creationism or following some arcane old covenant law, so following them or not has nothing to do with fundamentalism.

All this goes to say something very simple: that Christian fundamentalism is, I think, good. It is a problem, however, when one confuses the fundamental for the peripheral. That which was meant to be at best a tiny corner, became the centerpiece. No wonder the whole lot was ruined.

Thursday 6 March 2014

Reason, Experience, and Christianity

|

| Richard Feynman |

I wish to explain my position here in brief. It is not quite a full picture, and like most things outside of logic and mathematics, it is difficult to see how it can be made objectively normative. Furthermore, it completely omits the sorts of arguments and pathways that led me to some of the premises in this framework originally - a path that involved the methodological scepticism of Descartes, some study of philosophy, history and science. That story would be my best attempt at a foundationalist approach to Christianity - and I think it gets one relatively far, certainly to the point of being some sort of Christian. But it does not truly ever arrive at Christianity. I have instead found the position I hold now to be far more compelling and satisfying, even if it will alienate certain conversation partners.

To begin, I must quickly introduce what epistemologists mean by knowledge. Precise definitions vary because of some rough edges, but the classical definition still holds relatively firmly: knowledge is true and justified belief. That is to say, that some proposition constitutes knowledge in the case that the knower believes the proposition (one cannot know what one does not even believe), the proposition is in fact true (one cannot know a falsehood) and finally, one is justified in believing the proposition. What separates knowledge from belief is that the belief is true, but perhaps more importantly, that the knower actually has sufficient reason, or justification, to believe the proposition. Not surprisingly, some of the fiercest debates in epistemology seem to be around theories of what constitutes justification.

Very simply, I will term my position Christian reliabilism. Reliabilism, in the sense in which I will use it, refers to an epistemological theory of justification which says, in a somewhat crude form, that a belief is justified if it arises from generally truth-giving (or "reliable") faculties or sources, in the absence of evidence to the contrary. For example, I am justified in believing that I am sitting on a chair because I sense that this is the case with my sense of touch and sight. If there were evidence that I was dreaming, then I would no longer be justified in believing I am sitting on a chair.

Reliabilism is a broad family of theories of justification, and can actually be used in a broader sense than just justification. One reason it is powerful is that it is probably the only practical theory: the two other major families of competing theories are foundationalism and coherentism, both of which are excellent, but neither of them can really be thought of as "day-to-day" theories of justification. Foundationalism is very intuitive for people like myself who study mathematics, since it consists of the view that knowledge is built out of self-justified, basic beliefs. These could be said to correspond to what mathematicians call axioms. Descartes is surely the most famous and clearest foundationalist. Coherentism is a less ancient theory, but it is one which tends to appeal to scientists (as well as others) because it holds to a view that is somewhat similar to the approach taken in the natural sciences: coherentism is about finding justification in a coherent set of beliefs. A belief is justified if and only if it forms part of a coherent set of beliefs. Although the natural sciences involve other principles, such as Occam's razor, that a theory be coherent with all the data (both the data that has already been obtained, and the results that the theory predicts) is what defines a good scientific theory.

I struggle to see how truly self-justifying propositions can form a proper basis for knowledge without an impractical degree of scepticism. I doubt that even such basic things as the existence of the external worlds, or other minds, or perhaps even of the self, could be proven from self-justified propositions. So whilst I am drawn to foundationalism by my mathematical training, I cannot support it as a practical theory of justification. Coherentism is a theory I would be biased towards accepting, since its internalist structure makes it fairly straightforward to be a Catholic. But alas, I cannot see how it can be ultimately defended; it has elegance, but I see no way of bridging the gap between what reality seems to be in itself, and a coherent set of propositions. Elements of coherentism feature to some extent in many forms of reliabilism, however, and so coherentist theory may appear implicitly in what follows (in particular, note that the clause "without evidence to the contrary" given above in regards to reliabilism is essentially a statement about coherence).

Now, what constitutes a reliable faculty or source of truth is the area where Christian reliabilism is set apart from non-Christian reliabilists. It considers there to be three broad sources of truth: reason, experience, and Christianity. Reason is reliable as a source of truths, for instance, in mathematics or logic. Experience, by which I mean sensorial experience or experience of the empirical, is a reliable source of truths, for instance, in the natural sciences. God is a reliable source of truths in all areas, though I do not know of anyone who argues that God is a source of truths in actuality, since God is generally said to have revealed things of a particular kind, if any.

Probably the first objection one might have to adding divine revelation to the old empirical-rational duo of reliable sources is that divine revelation (sometimes called special revelation, or hereafter, just revelation) does not build off the others. However, whilst that line of critique would be fruitful if I were advocating foundationalism, it is somewhat irrelevant to a reliabilist. This can be seen from mere consideration of the other two: someone who denies the existence of the external world could just as well argue that experience is not a reliable source of truth, because it is not giving truths about anything that actually exists. Arguing that reason is a reliable source of truth is more difficult, because all arguments make inferences that are deemed valid by reason, but somebody stuck with a Cartesian demon would, nonetheless, doubt their own capacity for rationality. At bottom, both reason and experience must be deemed to be properly basic by the reliabilist - the foundationalist may mutter in despair, but they can do no better.

The Christian reliabilist, then, adds God to the list of properly basic reliable sources, and specifically, God as revealed in Christianity. Supposing God to exist, it seems obvious that God is a reliable source of information. Furthermore, there exists an parallel between the existence of the external world and the existence of God: whilst I think the existence of God can be proven, many dispute that arguments I find sound truly are sound, just like how philosophers such as G.E. Moore believed they could prove the existence of the external world, and yet, many dispute the arguments he offered (including myself). It could be said that, like the existence of the external world, the existence of God must be assumed. Whilst I have some discomfort at holding that position, particularly since I think the existence of God can be proven,* it can nonetheless be held with intellectual rigour, so long as it is granted that one is justified in believing in the existence of the external world without a priori proof.

The second objection is far more substantial, in my estimation: I have used God-as-reliable-source and Christianity-as-reliable-source somewhat interchangeably. But they are not the same, as a Muslim or Jew (et cetera) would inform. The same point made above could be a fruitful venture, that is to say, that one must assume Christianity to be properly basic, and yet, that route is supremely unsatisfying. The most obvious reason why that is the case is that the truth of Christianity is not like the truth of the existence of the external world, or God, but of a choice between multiple different competing sources for the title of divine revelation.

The difficulty could be resolved by trying to dip into the other theories of justification: I could attempt the foundationalist route, as I did when I became Christian, and argue from historical Jesus studies, in particular, any evidence for the resurrection. A similar approach could be taken for some other path from reason and experience to Christianity in terms of foundationalism, although I cannot think of any that are uniquely Christian and sufficiently powerful.

Or via the coherentist one, I could assume that God has "spoken" through some religion, and test them all to see which presents itself as most coherent. That the union of secular fields of knowledge and Christianity yields a powerfully coherent set of propositions, including with historical Jesus studies, keeps my mind at rest whenever I have major doubts about things, and yet, as I said, coherentism leaves me unsatisfied in general as an epistemic justification theory.

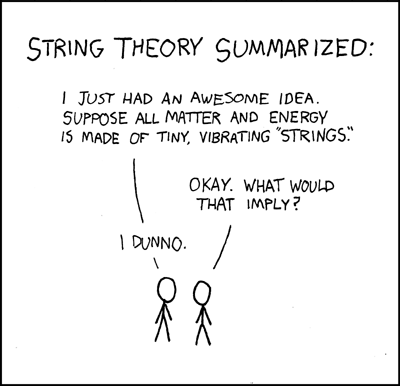

This second objection is not, in any case, unsurpassable since one could in principle assume Christianity is properly basic. Objections such as "given Christianity is true, what follows?" - in the same vein as the satirical xkcd comic strip on string theory below - are also important.

As one person noted to me, there is an important problem of interpretation: creedal statements like "Jesus is the Son of God" can be variously understood. What does it mean to be the Son of God? (One would naturally jump to some sort of sexual reproduction, which at least to some extent, would be completely mistaken) What does that imply about Jesus, other than origin? (The Arians, for instance, generally did not deny Jesus' sonship, but they did deny his divinity). If there is a difficulty in interpretation, there is a difficulty in understanding what is said to actually follow from the view that Christianity is a reliable source of truth. To a large extent, but not fully, this objection is met by Catholics in reminding the protester that the Church is herself a "living voice" - Christianity, in the view of Catholics, is not a religion of the book. As the Catechism quotes St Bernard saying: Christianity is the religion of the "Word" of God, "not a written and mute word, but incarnate and living". (CCC 108) And yet, that does not always yield perfect interpretation.

So Christian reliabilism has some issues that remain outstanding. Still, I contend that they are largely rough edges which can be fixed. One issue, however, remains crucially outstanding: Christian reliabilism is not objectively normative. By that I mean, whilst I can hold to it with intellectual rigour, I see no reasons within the system that would convince someone who did not hold to it. Whilst the same could be said, once again, about those who deny the existence of the external world, and to a large extent, absolute objective normativity is generally not thought to be possible, this is a theory which involves a much more ambiguous series of entry points. To this issue, I will return at a later date.

* It is actually a de fide teaching, I am told, of the First Vatican Council. Strictly speaking, though, since God is beyond what the usual arguments show (except, were it sound, the ontological argument), I do not believe the existence of God can be proven, only the existence of a being which is remarkably like God.

Friday 10 January 2014

Christian Vegetarianism? A Reflection and Review of "For Love of Animals" by Charles Camosy

Book finished on January 2nd, 2014. Disclaimer: I ignore some parts of Camosy's treatment of the issue in this piece, and expand on it with my own thoughts - please read the book to understand what Camosy writes on the topic.

I heard about the argument of this book a from a brief news article that I read in late October, 2013. I thought to myself, "hey, there might be something in this", added the book to my rather long booklist, and I suspected I would get round to it within the next few years. Something tickled my curiosity, though: did a consistent ethic of life really include animal life? Surely by "life" one meant "human life", after all, even bacteria are alive, and nobody argues for duties towards bacteria (unless they benefit whoever has them).

Near the end of November, a friend who had it messaged me telling me that the book was great, "very challenging, definitely going full on veggie now. Will bring it next time I see you." This chap certainly seemed to have been changed in a quite meaningful way by the message of the book, and even though people seem to be convinced by all sorts of oddities, I doubted he would be altered by any old nonsense - so, given that he was going to lend it to me, I thought I would bump it up my list. It could hardly hurt to explore the idea of vegetarianism inspired by Christianity.

Near the end of November, a friend who had it messaged me telling me that the book was great, "very challenging, definitely going full on veggie now. Will bring it next time I see you." This chap certainly seemed to have been changed in a quite meaningful way by the message of the book, and even though people seem to be convinced by all sorts of oddities, I doubted he would be altered by any old nonsense - so, given that he was going to lend it to me, I thought I would bump it up my list. It could hardly hurt to explore the idea of vegetarianism inspired by Christianity.

At only about 150 pages, it only took a few hours to read - some late at night (or the morning of the 2nd) and the rest after I got up from bed. It seems to be one of those books which are easy enough to read, but one has to think about whether or not the thesis is as sensible as one was lead to believe as one read. At its core, I think For Love of Animals is, whether fortunately or unfortunately, quite compelling, even if I disagree on some points.

The book could be divided into two parts, the first being a look at Christian views on non-human animals in the past, in the tradition, and the second half looking at now, today, and what we should do about the current situation.

To begin a book about a moral relationship with other animals, however, Camosy has to step back a bit and ask: what, as a Christian, constitutes an ethical treatment of anyone, be it dog, a woman, a black person, or even oneself? So he starts with something which is central to Christianity, and it is justice. He notes flat out, "perhaps one reason why questions of justice are often so difficult to discuss - and provoke such strong reactions - is that a genuine concern for justice means that we might risk rethinking our familiar and comfortable ways of seeing the world." (p. 3) Uh oh. That sort of sentence always seems to preface arguments with conclusions that would be highly inconvenient if true - think of the slave traders or owners being confronted with anti-slavery arguments. It's not enough to appeal to one's legal rights, or the majority concensus - it is the heart of rationality that sound arguments have true conclusions, and true conclusions must be followed. Whether it be the misguided language of slavery "rights" or abortion "rights", justice makes demands on our liberty and autonomy which are very often inconvenient.

Whilst I think the last sentence as an add-on is a bit awkwardly phrased as a definition, and I would prefer justice to be couched in terms of duties and not rights (or being "owed" something), this definition does seem to be the correct product of a Christian deliberation on the justice made manifest in Jesus Christ: "Christian justice means consistently and actively working to see that individuals and groups - especially vulnerable population on the margin - are given what they are owed. It will be especially skeptical of practices which promote violence, consumerism and autonomy." (p. 7)

And so he turns to animals: what does justice towards animals entail?

He knows that justice for animals sounds like a strange concept to most, and probably associated with anti-Christian animal rights activists. But, he says, we already have a basic intuition for the duty of kindness towards animals, for instance, when we hear of horrendous abuse of pets (just google images for "animal abuse" if you have never heard of such cases) or other animals, we intuitively respond with compassion, with moral outrage.

Still, he knows he has to dedicate a chapter to defending the idea that non-human animals even make it to moral status. He goes through the Christian tradition briefly and notes all the sorts of creatures who have moral status, yet are not human - angels, for instance, and that mysterious reference to nephilim might refer to non-human animals with moral agency. Moreover, people are beginning to consider the hypothetical of aliens - a little bit crazy at the moment, but not outside the imaginable - and they may too have moral agency. The point is not so much a defence of the existence of these beings, but that it is still conceivable that non-human animals be accorded with moral status.

Sure, so we do not exploit angels or aliens or whatnot. But animals? They were given to us to eat, right? Well, yes and no. The Edenic state appears to be quite pointedly a vegetarian (probably even vegan) one, and it is not until after the Fall that eating animals is acceptable. Is this total permission, or accomodating permission - by which I mean, is it like the permission to eat from any tree in the garden (except one), or is it like the permission to own slaves? It is unclear, and although Camosy spends a little more time on it, I think his argument will ultimately be unaffected by the distinction.

He makes an important point about creation, though, which is worth pausing for a moment to consider: whilst we frequently think otherwise, creation is not about or for us. All of creation, including animals, are said to be good entirely independent of humankind. We are to have dominion over it, be caretakers of it, subdue it and make it fruitful - that is to say, with all these activities we are to partake in the creative nature of God. I will write elsewhere about the clear Temple and Covenant motifs which appear and re-appear in discussions of creation (Genesis and elsewhere), but the basic point is a rather obvious one, that just because we live on God's green earth, does not mean we have absolute property rights. We are stewards entrusted with creation. We have broken this covenant of care, and so Christ has had to redeem not only us, but the whole of creation, which now "waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time." (Romans 8) And that was before the industrial revolution!

This is a part of the Catechism which is likely to be expanded in the years to come with new encyclicals and the exercise of the ordinary Magisterium as it addresses the destruction humanity unleashes on the world, not least to do with our effects on the climate, on natural treasures and the conservation of natural habitats - but nonetheless, the Church is not silent on care for creation. The relevant section is CCC 2415-2418 (bold mine): "The seventh commandment enjoins respect for the integrity of creation. Animals, like plants and inanimate beings, are by nature destined for the common good of past, present, and future humanity. Use of the mineral, vegetable, and animal resources of the universe cannot be divorced from respect for moral imperatives. Man's dominion over inanimate and other living beings granted by the Creator is not absolute; it is limited by concern for the quality of life of his neighbor, including generations to come; it requires a religious respect for the integrity of creation.

I heard about the argument of this book a from a brief news article that I read in late October, 2013. I thought to myself, "hey, there might be something in this", added the book to my rather long booklist, and I suspected I would get round to it within the next few years. Something tickled my curiosity, though: did a consistent ethic of life really include animal life? Surely by "life" one meant "human life", after all, even bacteria are alive, and nobody argues for duties towards bacteria (unless they benefit whoever has them).

Near the end of November, a friend who had it messaged me telling me that the book was great, "very challenging, definitely going full on veggie now. Will bring it next time I see you." This chap certainly seemed to have been changed in a quite meaningful way by the message of the book, and even though people seem to be convinced by all sorts of oddities, I doubted he would be altered by any old nonsense - so, given that he was going to lend it to me, I thought I would bump it up my list. It could hardly hurt to explore the idea of vegetarianism inspired by Christianity.

Near the end of November, a friend who had it messaged me telling me that the book was great, "very challenging, definitely going full on veggie now. Will bring it next time I see you." This chap certainly seemed to have been changed in a quite meaningful way by the message of the book, and even though people seem to be convinced by all sorts of oddities, I doubted he would be altered by any old nonsense - so, given that he was going to lend it to me, I thought I would bump it up my list. It could hardly hurt to explore the idea of vegetarianism inspired by Christianity.At only about 150 pages, it only took a few hours to read - some late at night (or the morning of the 2nd) and the rest after I got up from bed. It seems to be one of those books which are easy enough to read, but one has to think about whether or not the thesis is as sensible as one was lead to believe as one read. At its core, I think For Love of Animals is, whether fortunately or unfortunately, quite compelling, even if I disagree on some points.

The book could be divided into two parts, the first being a look at Christian views on non-human animals in the past, in the tradition, and the second half looking at now, today, and what we should do about the current situation.

To begin a book about a moral relationship with other animals, however, Camosy has to step back a bit and ask: what, as a Christian, constitutes an ethical treatment of anyone, be it dog, a woman, a black person, or even oneself? So he starts with something which is central to Christianity, and it is justice. He notes flat out, "perhaps one reason why questions of justice are often so difficult to discuss - and provoke such strong reactions - is that a genuine concern for justice means that we might risk rethinking our familiar and comfortable ways of seeing the world." (p. 3) Uh oh. That sort of sentence always seems to preface arguments with conclusions that would be highly inconvenient if true - think of the slave traders or owners being confronted with anti-slavery arguments. It's not enough to appeal to one's legal rights, or the majority concensus - it is the heart of rationality that sound arguments have true conclusions, and true conclusions must be followed. Whether it be the misguided language of slavery "rights" or abortion "rights", justice makes demands on our liberty and autonomy which are very often inconvenient.

Whilst I think the last sentence as an add-on is a bit awkwardly phrased as a definition, and I would prefer justice to be couched in terms of duties and not rights (or being "owed" something), this definition does seem to be the correct product of a Christian deliberation on the justice made manifest in Jesus Christ: "Christian justice means consistently and actively working to see that individuals and groups - especially vulnerable population on the margin - are given what they are owed. It will be especially skeptical of practices which promote violence, consumerism and autonomy." (p. 7)

And so he turns to animals: what does justice towards animals entail?

He knows that justice for animals sounds like a strange concept to most, and probably associated with anti-Christian animal rights activists. But, he says, we already have a basic intuition for the duty of kindness towards animals, for instance, when we hear of horrendous abuse of pets (just google images for "animal abuse" if you have never heard of such cases) or other animals, we intuitively respond with compassion, with moral outrage.

Still, he knows he has to dedicate a chapter to defending the idea that non-human animals even make it to moral status. He goes through the Christian tradition briefly and notes all the sorts of creatures who have moral status, yet are not human - angels, for instance, and that mysterious reference to nephilim might refer to non-human animals with moral agency. Moreover, people are beginning to consider the hypothetical of aliens - a little bit crazy at the moment, but not outside the imaginable - and they may too have moral agency. The point is not so much a defence of the existence of these beings, but that it is still conceivable that non-human animals be accorded with moral status.

Sure, so we do not exploit angels or aliens or whatnot. But animals? They were given to us to eat, right? Well, yes and no. The Edenic state appears to be quite pointedly a vegetarian (probably even vegan) one, and it is not until after the Fall that eating animals is acceptable. Is this total permission, or accomodating permission - by which I mean, is it like the permission to eat from any tree in the garden (except one), or is it like the permission to own slaves? It is unclear, and although Camosy spends a little more time on it, I think his argument will ultimately be unaffected by the distinction.

He makes an important point about creation, though, which is worth pausing for a moment to consider: whilst we frequently think otherwise, creation is not about or for us. All of creation, including animals, are said to be good entirely independent of humankind. We are to have dominion over it, be caretakers of it, subdue it and make it fruitful - that is to say, with all these activities we are to partake in the creative nature of God. I will write elsewhere about the clear Temple and Covenant motifs which appear and re-appear in discussions of creation (Genesis and elsewhere), but the basic point is a rather obvious one, that just because we live on God's green earth, does not mean we have absolute property rights. We are stewards entrusted with creation. We have broken this covenant of care, and so Christ has had to redeem not only us, but the whole of creation, which now "waits in eager expectation for the children of God to be revealed. For the creation was subjected to frustration, not by its own choice, but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be liberated from its bondage to decay and brought into the freedom and glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time." (Romans 8) And that was before the industrial revolution!

This is a part of the Catechism which is likely to be expanded in the years to come with new encyclicals and the exercise of the ordinary Magisterium as it addresses the destruction humanity unleashes on the world, not least to do with our effects on the climate, on natural treasures and the conservation of natural habitats - but nonetheless, the Church is not silent on care for creation. The relevant section is CCC 2415-2418 (bold mine): "The seventh commandment enjoins respect for the integrity of creation. Animals, like plants and inanimate beings, are by nature destined for the common good of past, present, and future humanity. Use of the mineral, vegetable, and animal resources of the universe cannot be divorced from respect for moral imperatives. Man's dominion over inanimate and other living beings granted by the Creator is not absolute; it is limited by concern for the quality of life of his neighbor, including generations to come; it requires a religious respect for the integrity of creation.

Animals are God's creatures. He surrounds them with his providential care. By their mere existence they bless him and give him glory. Thus men owe them kindness. We should recall the gentleness with which saints like St. Francis of Assisi or St. Philip Neri treated animals.

God entrusted animals to the stewardship of those whom he created in his own image. Hence it is legitimate to use animals for food and clothing. They may be domesticated to help man in his work and leisure. Medical and scientific experimentation on animals is a morally acceptable practice if it remains within reasonable limits and contributes to caring for or saving human lives.

It is contrary to human dignity to cause animals to suffer or die needlessly. It is likewise unworthy to spend money on them that should as a priority go to the relief of human misery. One can love animals; one should not direct to them the affection due only to persons."

I have largely skipped over Camosy's discussion of the Christian tradition's engagement with non-human animals, as well as statements from recent Popes, holy people and saints, and entirely omitted almost all discussion of the Sacred Scriptures. These are relevant, and raise some potentially thorny questions, to which proper response must be given in due time. For now, the Catechism's summary of care for creation should be sufficient for Catholics. I want to turn, then, to the practical application of these ideas; of Christian justice, stewardship of creation, and the teaching of the Catechism. Camosy's conclusion is probably slightly stronger than the one I am going to give here, but the weaker version will suffice:

It is quite clear that the Catechism permits eating animals. I need not argue that this is merely a circumstancial liberty (like owning slaves) that will be erradicated later on. I wish to point out instead that the Catechism moderates the claim by pointing out that it is nonetheless wrong ("contrary to human dignity" - that is, a violation of our intrinsic ideal and purpose) to cause animals to suffer or die needlessly. One must ask, given the quite deplorable conditions from which a substantial portion of our meat comes - not all, and in Australia we are a bit luckier - does spending money to fuel the factory farming industry constitute a real need? I cannot see any justification for it. Note that this is not a conclusion that rejects eating meat outright - it objects to excessive meat consumption (which would constitute needless death) and particularly to the way in which animals are caused to suffer in order to maximise profits for the farm in question. Just because I am well known for advocating that standard logical form be used more often in these discussions, the argument could be expressed:

1. If it is unnecessary to cause an animal to suffer and/or die, then causing it to suffer and/or is morally wrong.

1. If it is unnecessary to cause an animal to suffer and/or die, then causing it to suffer and/or is morally wrong.

2. The meat that is eaten comes predominantly from animals that have suffered needlessly (in particular, from factory farms).

3. Needless buying and consumption of that meat is cooperation with, and subsidy of, the moral wrong of premise 1.

4. Therefore, needless buying and consuming of that meat is wrong.

The conclusion is not as universal as "meat eating is wrong." It is far more measured: supposing that eating the meat does not constitute a need (which, for most of us, it does not), and supposing the animal did suffer and die needlessly (highly likely, but not guaranteed), then such meat eating is morally wrong.

Not eating meat is hard, and no matter how many reasons are given (sustainability, an eschatological observation, personal health, environmental, et cetera), the social structures that exist in the world, in our families and in our wider communities do not favour vegetarianism. Particularly for men: vegetarianism is seen as effeminate and hence negative, a violation of our proper steak loving manliness. Traditional family meals all tend to have meat - Christmas meals, for instance. The argument I have given, however, demands either our assent or the rejection of its soundness - although I note again, not all meat eating is made bad by that particular argument. If one can get an animal that did not suffer needlessly, and that did not die needlessly, then as far as this argument is concerned, eat away! Perhaps that means a rather large cost - but that is fine, succumbing to cheap meat qua cheap meat would be formal cooperation with injustice, it would be failing to pay our debt of kindness to animals, and hence, wrong. Camosy would probably want to go further than that, but at present, I am only comfortable assenting this far.

The issue at hand, to conclude, is one of justice. Christians of all people should lead firmly by example into new depths of justice, kindness, and care for what God has entrusted to us.

Friday 28 June 2013

The Road From Unbelief

"The way I see it, these days there is a war on, and ages ago there wasn't a war on, right? So, there must have been a moment where there not being a war on went away, right? And there being a war on came along. So what I want to know is, how did we get from one case of affairs to the other case of affairs?"

That is a very long way of asking how the war started, but in some ways, it's making a more accurate question: because "how did we change states of affairs?" sounds like a process. And a question about the process is exactly the right question for how WWI began.

Similarly, I cannot conceive of my becoming a Christian as anything other than a process. "When and how did you become a Christian?" is a misleading question, since no precise time or methodology can be named, whereas "what process led to your conversion?" is much more answerable.

I was raised atheist in England and Spain, mainly, in a lower middle class household to a Chilean dad and English-Australian mother. The only times religious things that were brought up in my family were a couple of comments made by my dad about some Jehovah Witnesses[1] that he coached tennis for, some other comments made by him around Christmas time about how Christmas should not be about presents, bringing up how Jesus was humble and not materialistic (which led to going to a midnight church service a couple of times, but I do not remember anything from there), a storybook of David and Goliath[2], and probably a few other times that have slipped my memory. The point is, it was not a religious, or anti-religious, upbringing. It was a caring, secular environment.

Having never been taught or told anything religious, I nonetheless developed into quite the atheist. Particularly in Spain, my friends were all atheists with two exceptions (perhaps three, but the third was an atheist in terms of daily life and attitudes), even though many of them had been through confirmation and first communion, and all except for one had been baptized. I knew there were religious people around, I just didn't have any contact with them. I thought religion was a childish thing that humankind had inherited from its history. In my diary from when I was fifteen I wrote (this is dated 13-XI-2009 (Friday) at 8:52 AM in my Lengua or Language and Literature class):

"God. The idea of god is as old as mankind. Since the beginning, God or Gods have been used to explain things without explanation.

For example, the Ancient Greek and Roman Gods. Zeus was the god of lightening and thunder. Storms of this kind were chalked up to divine intervention.

Monotheism is far newer. Most religions practiced in modern times have only one God, although by different names:

In Islam, it's Allah.

In Christianity, it's just "God."

In Judaism, it's God, or Yahweh, the Hebrew word.

All these religions have a lot more in common than commonly thought.

The Holy book of the Jews, the Torah, and other scriptures (they have 5 books) makes up the old Testament of the Bible, which is the Christian Holy Book. What does that mean? It means that Jews abide by the same rules as Christians do.

In fact, Christianity proceeds from Judaism. It was formed by a break-away from Jewish beleifs, and Christ himself, prophet of Christianity, was a Jew.

So how did Christianity develop to almost "rival" Judaism, when All The Bible comes from the Jews.

Well, I think it's for the same reason the Church of England, and the Protestant ways, broke from the Roman-Catholic Church.

It brings power and individuality to a religion. If you follow a certain idea, you are bound by it. However, if you create your own ideals, based on another, you are free to develop it, and that means power.

..."

I went on in that entry in my diary to articulate some of the differences in ideology between Christianity and Islam, and how it reflects in the judicial practice of the culture. There are factual errors (the Torah has 5 books, but the Old Testament has more), theologically dubious claims (that Jews and Christians have the same rules) and errors in spelling, but this was my understanding of religion: that God was originally an explanation for phenomena and the newer monotheism was more sophisticated (though still nonsense) where people believed some particular book was holy. I also thought it was weird that people fought so much when they mostly believed the same thing. In general, by the time I turned sixteen, I was decidedly anti-religion.

So how I became a theist, and then a Christian, seems like a very important question to me. What led to my conversion?

The reasons why I suddenly became more critical of my beliefs - which I assumed to be the rational ones, as so many still believe unquestioningly (see here for more on that) - and think about reality, as well as my place in it, is unclear. The usual story I tell has to do with how I enjoyed physics so much that I couldn't explain it, and found my love for it unreasonable, leading me to question whether there was any value in studying physics, but I think that's just an illustration of various things that were bubbling under the surface. The reality is, I'm not quite sure why I decided to think more. But I did.

To avoid being accused of falling into the cultural religion, I explored Islam first. Though some of the ideas seemed reasonable, I did not find the system of belief compelling, the manner in which it arose to be endearing or the treatment of aspects of reality as illuminating, that is, that it seemed more like man-made theological philosophy with a holy book than the divine revelation to man. At some point during this time, however, I began to find it reasonably tenable that God should exist. A prime-mover God, but God nonetheless. I still find the first-cause argument compelling, and the ontological (modal) argument to be a very interesting one for agnostics, though I am unsure whether I should believe in modality or not, and the first premise has the potential for a fallacy of equivocation between two ideas of possibility (known sometimes as epistemic possibility and broadly logical possibility).

It may never cease to amuse me how I got on to the Christian faith. I was told that to completely disprove the biggest religion in the world, and be able to ridicule all the adherents I had ever known and would meet, I just had to look into history and show that the resurrection never happened. Christianity hinges on this one fact, so my first thought was "brilliant, that will be quick, people do not come back from the dead." Which is mostly true, but as I trawled scholarship and the evidence, I became convinced that Jesus had in fact risen from the dead.

Now, may I point out something important: it is not proven historically that Jesus rose from the dead. Ancient historical studies do not work in terms of proof - only mathematics and logic do that. Newly found belief in God meant that I did not think such an occurrence was impossible, though indeed, to assume it is impossible for someone to be raised from the dead would be to beg the question on the matter of the historicity of the resurrection. I find the resurrection to be the most rationally compelling explanation for the facts, and I have not got philosophical barriers to considering it an option.

To end, there are notable but rare examples of people who believe in the resurrection but are not Christians, but for the most part, to believe in the resurrection is to be Christian of some sort. Essentially, this was the beginning of my being Christian: believing in the resurrection from the dead, heeding therefore what I thought Jesus would have said (which meant applying historical criticism to the gospel accounts), and finally ending up believing that the Scriptures were a reasonably solid thing, at least the New Testament, which I had then read. It can be said that I at least believed the first part of the Apostle's creed (the part in bold):

"I believe in God the Father almighty, Creator of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ his only Son, our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried. He descended into hell and on the third day he rose again from the dead. He ascended into heaven, and sits at the right hand of God, the Father almighty. He shall come again to judge the living and the dead. I believe in the Holy Spirit, the Holy Catholic Church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body and life everlasting."

The second part of this four part series can be found here.

[1] Perhaps

because of this, my dad does not quite believe me when I say that virtually all

Christians believe Jesus is fully God.

[2] In my memory of this book, it was a completely secular story about how underdogs can win - but since we still own it, I checked and it does in fact reflect the faith of David coming against the Philistine Goliath.

[2] In my memory of this book, it was a completely secular story about how underdogs can win - but since we still own it, I checked and it does in fact reflect the faith of David coming against the Philistine Goliath.

Friday 7 June 2013

The Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-12)

One of the archetypical pictures of Jesus is him giving the beatitudes - a series of blessings to certain groups of people. There is another, shorter set in Luke's gospel, which I can use redaction criticism on later on and compare the two. For now, let me centre on St Matthew's account. Allow me also to note how these blessings fit into a covenantal framework in which Jesus operates: when covenants are made, their clauses have covenant blessings for those who are faithful to it, and covenant curses to those who are unfaithful to it. These are then the new covenant blessings, I think, which should be contrasted with the new covenant woes (or curses) later on.

"Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven." (v. 3)

This term "poor in spirit" is interesting in that poor generally means "lacking in [...](usually money)", but "lacking in spirit" is an English idiom equivalent roughly to being downcast. Since this is a modern idiom, I doubt this interpretation is right. Some have interpreted it to mean those who are materially poor, which fits with God's care for the poor as seen throughout the Old Testament, but that interpretation ignores the in spirit bit.

My interpretation goes something like this: blessed are those who realize their spiritual poverty. That is, not so much those who lack a spirit as some kind of entity, but more, those who are spiritually humble, who recognize their spiritual deficit. One objection to this is that, in reality, everyone is poor in spirit before God, so by that measure, everyone's is the kingdom of heaven. I do not think this objection is a good one, since this is a public sermon in which people are going to be relating these terms to themselves. Some of the audience will think "truly I am poor in spirit", and then be contented by the blessing, but others (and St Matthew probably has the Pharisees in mind) will think of themselves as rich in spirit. The distinction between the two is whether or not they recognize it - but of course, that makes a great deal of difference in practice.

Yet that is not all - I run this risk of over spiritualizing this beatitude if I make it only about knowledge of spiritual poverty, but no more. Being poor in spirit entails not only recognition of that, but also recognition of the material lack. That is to say poor in essence. Material poverty is included because this recognition of "I have nothing before you, God" extends to both the spiritual and the material.

"...theirs is the kingdom of heaven" From my interpretation, it follows that those who recognize their poverty, both spiritual and material, are the ones who will inherit the kingdom of heaven.

"Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted." (v. 4)

This blessing highlights the sad, those who mourn - in general, people who mourn lack something. So I suggest that this blessing is a divine promise that those who do not think they have it all, those who are aware of their lack, will be comforted by God.

"Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth." (v. 5)

This blessing is the clearest example of the upside down kingdom which Jesus proclaims, because the meek are usually the ones trodden on the most - they are not rulers, instead they are the doormats of rulers in this age. Not so in the age to come, Jesus says, for they will inherit the earth! This is also a clear example of how Jesus' heaven is not ethereal and other-worldly; no no, Jesus the redeemer is going to redeem this earth, and give it as inheritance to the meek.

"Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled." (v. 6)

I suppose the best way to understand this is another "those who recognize they lack will be given to" statement, in that those who are not satisfied with the righteousness they have are the ones who will be given more. A similar sentiment can be found in 1 John where John says that those who are without sin make Jesus out to be deceitful - ahh, but those who sin and plead forgiveness have an advocate with the Father. This is another bid that we recognize our spiritual poverty, this time specifically our moral poverty, that we may hunger ever for more. [1]

"Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy." (v. 7)

It is unfortunate that Matthew was chosen as the first gospel to be read in this reading plan, because it has such richness that points back to the Old Testament. It is, after all, the "Jewish gospel" - and that means it requires even more context. This word "mercy" is one of those key words, I believe, which would gain enormous profundity if the reading plan had covered more of the Old Testament by this point. Not to worry, though, because the common-sense reading is already rich: Jesus blesses those who have mercy, saying that they will be had mercy on. This is not the same as "God will have mercy on you if you have mercy on others," but instead "Those who yearn for God's mercy are merciful." These beatitudes, I contend, should be seen as cumulative in the sense that I think Jesus is blessing the same group with each one. Therefore, I suggest that those will will receive mercy are merciful, over the interpretation "those who are merciful will (for this reason) receive mercy." These things are all attributes of those who will inherit the kingdom of heaven, who will see God, who will receive mercy - the attributes are not why they receive these things.

Let me stress another point, though: the merciful are not often thought of as the most forgiven. It is a sad fact of life that far too often, those who are forgiving get trampled on, not given mercy. So here too we see those who are full of mercy being given just what they yearn for themselves: mercy.

"Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God." (v. 8)

Uh oh. Nobody who really thinks they are spiritually impoverished also thinks they are pure in heart, I do not think. Has Jesus just alienated everyone?